Do Asian coffee professionals have a soft spot in their hearts for natural-processed coffees? Are there coffees that would be “defective” to a Colombian cupper, but considered a fine delicacy to a cupper in Shanghai? How can we communicate intelligently across cultural divides to become better coffee professionals, and to ensure that the right coffees reach the right markets?

I was teaching a coffee tasting course in Hong Kong a couple of years ago, when I had a revelation about the flavor of coffee — but it was not at the cupping table. Instead, my discovery about coffee came over a cup of tea.

My students were all very high level, and we were doing some intense palate-training exercises. On most topics, we understood each other well, despite a language barrier from English to Cantonese. But there was a certain flavor in one fine washed Panamanian coffee that students kept referring to as “oolong tea.” Now, I have had oolong tea before, in the United States and elsewhere. But it’s not a flavor I am very used to.

The next day, I met for lunch with some of the top coffee professionals, with traditional Chinese dishes and tea. “This!” said one of them, holding up his tea. “This is the taste I was talking about.”

I lifted the cup to my lips and tasted it, eyes closed. “Yes, of course,” I thought. There was a pleasant, sweet, and almost savory taste, reminscent of aromatic woods, like sandalwood. Suddenly, I could recall the flavor of the Panama coffee, and it all made sense.

This experience, of learning new ways to describe flavor from experiences and people outside your own cultural background, is something that is happening thousands of times a day, all around Asia and then wider world of coffee. There are huge differences between how Asians describe coffee, compared to North Americans, compared to Latin Americans, compared to Africans, and on and on. Most people you talk to are aware of these differences, but I am not aware of any systematic attempts to understand them.

As a Westerner working in specialty coffee in Asia, I decided to conduct a series of interviews with top coffee professionals around the region. I also conducted dozens of cuppings in the region, from Thailand to Shanghai, using coffees I know intimately, and carefully observed the results. There is still much to learn and explore, but I’ve started to reach a few tentative conclusions.

Your Experience Determines Your Vocabulary

When training cuppers, I often say, “All of you are already excellent, professional tasters. If you were not, you would be dead. You’ve been tasting things all your life, with perfect accuracy. What’s lacking is the vocabulary to describe your sensations.”

When doing formal cupping training, such as in the Q-grader program, there is a strong effort to standardize the evaluation, so that “8.25 acidity quality” from a cupper in Tokyo is the same as “8.25 acidity quality” from a cupper in Amsterdam. Of course, there are always small inaccuracies and differences of opinion between cuppers, but these attempts to create a “universal language of coffee” have been hugely successful and valuable so far. There’s always more work to do, but standardized cupping protocols have done much to bring the wide world of international coffee into one, mutually-intelligible set of terms.

Nevertheless, when people are training, or when they are talking to their friends, or when they are trying to communicate with their customers, they inevitably fall back on a vocabulary they have been learning their whole life. If a customer asks you to describe a coffee, you’d never begin, “Well, the acidity is 8.25.”

Rosario Juan, Owner and Chief Extractor of Coffee at Commune in Manila, Philippines, tells about a training with the expert Ethiopian coffee trainer, Daniel Mulu of CQI.

“There was this Honduran coffee that tasted like sinigang,” says Juan. “Of course he had no idea what sinigang was. It’s a Filipino dish — a sour broth, usually with beef, sometimes with prawns, and we use a souring agent for it. Usually tamarind, or young guava. It’s a sour soup, but it’s also kind of savory.”

The next day, Daniel went to a Filipino restaurant and ordered sinigang and said, “Yes, you were right. That coffee was a lot like sinigang.”

In my experience, Western cuppers will often identify certain coffees that have a complex acidity rich in phosphoric acid to taste like “tomato soup” or “beef broth.” You hear these terms used about fine Kenyan coffees, for example. Such terms can raise eyebrows among other cuppers, because beef broth does not sound very positive, but its usually reserved (by Westerners, especially North Americans) for very fine coffees.

This is just one example of how cultural biases and experiences can give us very strong, specific mental impressions, even though they also often make it more difficult to communicate those impressions to the rest of the world.

Korn Sanguankeaw, Head roaster of Roots Coffee, Bangkok, explains that often fruits that Westerners use to describe coffee, like plum, blueberry, and raspberry, are difficult for Thai cuppers to identify. “Our local cuppers are more likely to use local flavors to describe them.”

In fact, he even says that the Thai palate is more forgiving of sour flavors in coffee, and even astringency, because many preferred local fruits are indeed sour and astringent. So it’s not just a matter of descriptive words, but in fact a matter of perceived quality. A coffee that a Westerner might mark down for lacking sweetness and having too much astringency, a Thai cupper might be more forgiving with.

Something I’ve noticed among my many cuppings around Asia, is that a greater familiarity with certain fruits can lead to misunderstandings. For example, I had been cupping in North America, Latin America, and Africa for 10 years before I ever came to Asia. In all those years, I heard the terms “papaya” and “mango” reserved for only the most elite, exotic coffees, those scoring 90 and above.

When I came to Asia, I heard those terms used much more frequently. The Korean-born coffee training expert, Miran Oh, a head trainer for the Coffee Quality Institue and owner of Healing Coffee in Los Angeles, California, helped me understand this. Although Oh agrees that terms like mango and papaya are still positive notes in Asia, she says they don’t carry the same level of “elite” and “exotic” connotations that Westerners associate them with. A nice 84 point coffee can have hints of mango. Whereas if I told a Western cupper that I picked up mango in an 84 point coffee, he might say “Let’s not go crazy, Daniel!”

Preference… or Error?

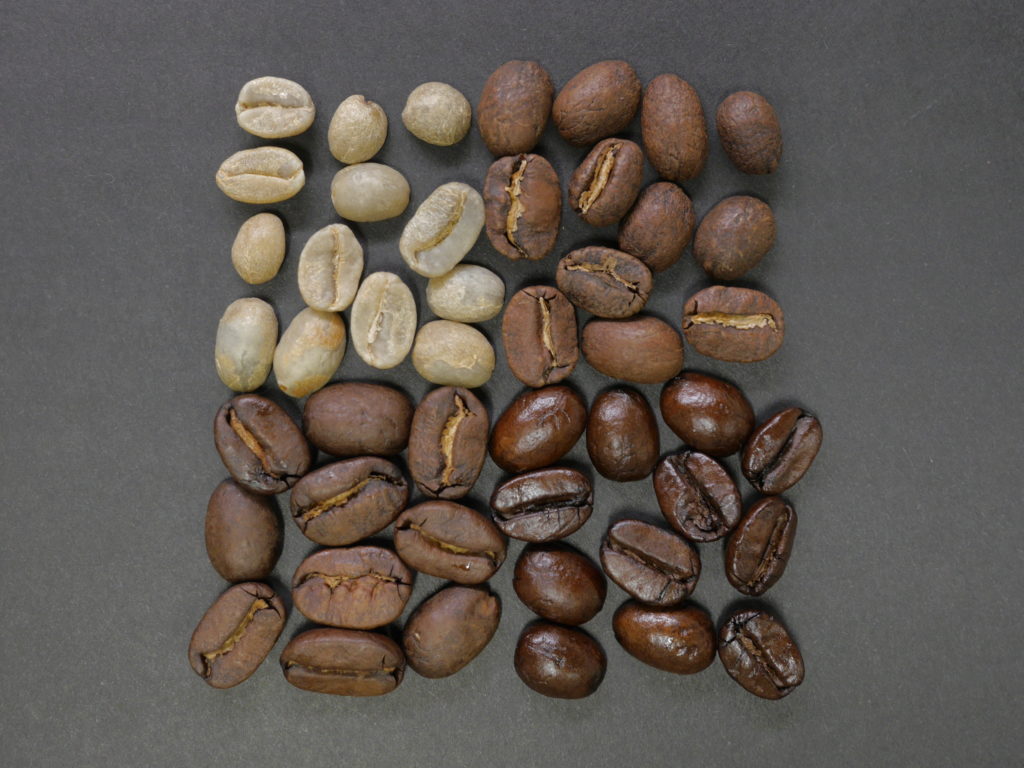

Sanguankeaw of Roots, Bangkok, also notes a marked preference for natural coffees, versus washed coffees, among Thai coffee people, something I have noticed as a larger trend in Asia as a whole.

Among Western and especially old-school Latin American cuppers, there exists what might be called a prejudice against natural coffees. Or to put it more charitably, a preference for the clear, clean, and bright flavors of high-quality washed coffees. Although, of course, many Asians love great washed coffees, too, on average, there is more demand for the full, earthy and fruity flavors of naturals.

Last year I purchased a coffee from Yunnan that would have been considered completely defective by a cupper from, say, El Salvador. It had an intense, sharp, winey acidity. Some cuppers identified it as over-fermented, even borderline phenolic. Other cuppers — especially Asian ones — found it delightful and scored it in the very high 80s. I purchased the coffee (and almost immediately sold out), because I realize it’s not my role to tell people their preferences.

Nevertheless, I’ve also seen too much tolerance to certain flavors, especially among cities with new and fast-developing coffee scenes, such as Singapore, Shanghai, and Beijing. Old, past-crop coffees that are frankly woody and stale, get passed off as “tea-like” or “herbal” (or even “ooh-long”!) That might work with unsophisticated customers, but as the status of the coffee industry in these cities increases, these kinds of mistakes will be inexcusable and embarrassing. That’s not “local preference,” that’s just an error.

It’s an exciting time for coffee in Asia. Things are growing at an astonishing speed. All the local preferences and terms make for a rich experience, both for professionals and for customers. There is also now a place for people who have cross-cultural understanding, who can communicate back and forth between the various “worlds” of coffee, from East to West, and especially to the producers in origin countries. Everyone benefits from this process, and the quality of coffee delivered only improves as a result.

NO COMMENT