Photo: Chris Kornman

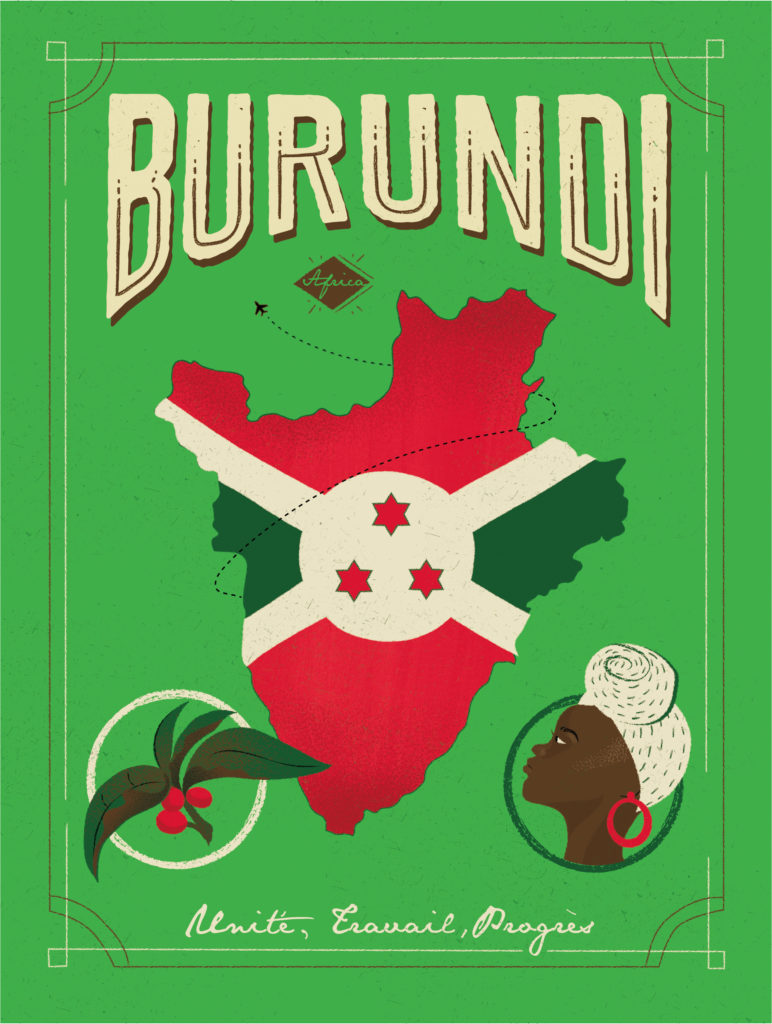

The clay is red as bricks, stark against the lush greens of banana trees, tea leaves, and coffee plants. The colors are reflected in the country’s flag, reds and greens and white like the wisps of clouds grasping for the peaks of the verdant hills as they pass.

At the center of Burundi’s flag is a Karyenda, a ceremonial drum, among the more important cultural icons. Particular instruments and rhythms mark the beginning of harvest, coronations, births, or funerals. It’s not uncommon to come across a circle of drummers and dancers practicing or offering a performance as a greeting.

Kayanza, running along the border with Rwanda, is rural and rugged, and home to some of the best coffee in Burundi. Like so much in coffee, my connection to Burundi started with a relationship and some good faith.

Illustrated by Xinjia Liu

I’d paid my first visit to the heart-shaped nation in the center of East Africa’s Great Lakes region in 2014, as an observer in a Cup of Excellence competition. We stayed in a small resort hotel in Bujumbura on the coastline of Lake Tanganyika (the planet’s second-deepest freshwater lake) drinking, walked to a few local coffee shops, tasted coffees from across the nation for the competition, sipped sugary Primus lagers in the evening paired with salty crispy fried lake fish that you could pop like French fries.

It was August, and the harvest was a distant memory, but we still visited a vacant washing station a thirty-minute drive from the capital. The whole experience was far more comfortable, curated, and closed in than I’d expected, perhaps for the best, given our primary purpose as quality evaluators for a competition.

I quickly started looking for a way to return and travel with fewer inhibitions. I reached out to a few contacts I’d made, but without working knowledge of the French language or Kiburundi, the local Swahili dialect, I was at a bit of a loss.

Photo: Chris Kornman

How exactly I’d caught wind of the man named Salum Ramadhan remains a bit of a mystery to me. We had two mutual acquaintances by the time we started talking about a visit. The first was in the US: Timothy Hill, directing the coffee program for Counter Culture in Durham, North Carolina, who I believe had gifted me a sample of really spectacular coffee that stuck with me, sourced from a place I could barely pronounce: Buziraguhindwa. I asked him how he’d feel about me connecting with the same producer, and his response was pleasantly magnanimous.

In the conversation, it became apparent that we had a second mutual friend, Sam Muhirwa, who runs BufCoffee in Gikanda, Rwanda. Muhirwa and I had met on numerous occasions, and I’d already been buying his coffee by the boatload for a few years. I began to plan my trip, with a brief initial contact with Ramadhan and the good faith promise from Muhirwa that yes, he could connect me, and yes, I could just walk across Rwanda’s southern border into Burundi. I booked my flight to Kigali.

Illustrated by Xinjia Liu

I’d travelled a bit in East Africa, mostly with local contacts who I’d learned to trust. This would be my first shot at laying the groundwork for a partnership with a producer whom I’d never met in person. The extent of our conversations was a couple of lines over the course of a few emails. I’d be lying if I told you I wasn’t a little nervous. The border between Rwanda and Burundi was quiet on the Monday afternoon where I left Muhirwa and walked past an armed guard or two, showed my passport, and paid the equivalent of about US$25 to enter Burundi.

This border didn’t always exist, certainly not in its current form. At present, it is mostly used by refugees fleeing poverty, violence, or starvation in Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Rwanda and Burundi were once a single territory called Ruanda-Urundi, recognized by colonizers from Belgium and Germany. Before that, of course, they were distinct and independent kingdoms with borders that may or may not roughly correspond with how Europeans arbitrarily carved up the land.

Burundi and Rwanda are so often mentioned in the same breath for more than just colonial history. They are two of the geographically smallest nations on the planet, and they share the same two major ethnic groups: Hutus and Tutsis.

You’ll likely recall the international attention given to the ethnic conflict between these groups that came to a violent apex in 1994 with a genocide that left hundreds of thousands of people dead and many more displaced. While the sparks that ignited the flames in these two areas were separate, the buildup in many ways was related to Belgian influence and has a deep-rooted history of conflict, ongoing civil wars, and violence predating the two nations’ independence in the 1960s.

Photo: Chris Kornman

In the wake of genocide in the two countries, international attention and aid were directed to the region, by and large focusing on Rwanda and ignoring Burundi, a truth that remains true to this day. Rwanda’s rapid economic growth and ongoing foreign investment cast a shadow on its southern neighbor, Burundi, who received only a fraction of the international attention, currency, and rebuilding efforts.

Thus, while Rwanda is emergent, Burundi has suffered. Ethnic violence and civil war remained realities in the country, and an estimated 65% of the Burundi’s citizens live below the poverty line, and it remains on top of the list of the world’s most undernourished nations.

Illustrated by Xinjia Liu

It wasn’t hard for me to see the difference in the faces of the people in Kayanza and of those across the border to the north in Rwanda. Kayanza and nearby Ngozi Province have seen far fewer people who look like me (pale skinned, blonde-haired, and of moderate means) and the children react with a distinctive “Mzungu”— a term used to denote otherness, foreignness. It’s mildly derisive and comes from a more literal translation that means “aimless wanderer”, a sort of white-zombie I suppose.

Ramadhan is quick to tell the crowd of children that’s gathered around us that he doesn’t approve of their shouting. We’re at his washing station, Buziraguhindwa (or just Buzira, if you like). It was his first, established in 2009. Since then he’s opened three more, each with a similar theme: high prices paid to the local smallholders for their coffee cherry delivery, immaculate infrastructure, well-managed procedures, and a small adjacent farm filled with different coffee varieties to use as an example of productive cultivars and good farm practices. His reach is incredible — between 2,000 and 3,000 local farmers contribute their coffee to each of his wet mills.

Photo: Chris Kornman

He beams with pride as we visit the cattle shed, his prized bovines low gently as he feeds them grass. I feel lucky to have found the man, his coffee exceptional, his practices sustainable, his manor absolutely magnanimous. Having never met me before he has invited me into his home. I get the sense following him through Kayanza town that he knows practically everyone and treats them all with kindness. He grew up here, in the country. Bujumbura is a rambling two- hour-plus drive to the south, the big city, the political center. His family lives there now but I sense his heart is here in Kayanza.

Kayanza is in the heart of Burundi’s coffee production area, second only to neighboring province Ngozi in total production volume. Coffee is the country’s leading export product, both by value (65%) and volume (90%), followed by tea, cotton, and sugar. The potential for quality arabica is incredibly high. Ideal climate and growing conditions combined with old-growth heirloom varieties yield exceptional flavors. Many farmers still grow legacy Bourbon cultivars; the most common local iterations are usually known as Mbrizi and Jackson.

I’ve met with others working coffee in Burundi; locals and expatriates both who help connect the rural farmers to the international coffee market. One of the more remarkable women working in the industry is Jeanine Niyonzima-Aroian, founder of JNP coffee and a passionate advocate for both her home country and women in coffee. Raised in nearby Ngozi, Jeanine’s connection to coffee runs deep. Her parents grew up picking coffee to help pay for their schooling.

Photo: Chris Kornman

Farmers working with such conscientious managers and export partners are lucky. Many others remain entrenched in poverty, as local stations change hands or collapse under mismanagement. On a recent visit Ramadhan pointed out a former Cup of Excellence (COE) winning wet mill, now in shambles. COE returned to Burundi after a few years break, along with Rwanda the only country in which ACE has established a regular quality competition and associated coffee auction. This has helped to increase international attention to the incredible quality already being produced in the country.

Yet quality-conscious coffee roasters often point to a single reason why they don’t buy more coffee from Burundi and Rwanda (or any at all, in some cases): Potato Taste Defect (PTD). It is a taste defect. It won’t make you sick, but it definitely presents strong off-flavor tastes and smells. Yet more than a mere nuisance, it can also cause severe economic problems for coffee producers. The potato defect is akin to an occasional bruised avocado you thought was ripe, or a corked wine bottle. In my opinion, given the quality of coffees from these areas, it’s a risk that’s totally worth the reward.

PTD has been found as a natural occurrence in certain East and Central African Great Lakes coffees, mostly in Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Uganda. It has been less frequently encountered in Tanzania, Zambia and Kenya. It holds no relationship to root vegetables other than the fact that coffee containing the defect tastes and smells quite a bit like raw potatoes. This is caused by a particular member of the chemical family of pyrazines, commonly produced by plants naturally. Some pyrazines found in vegetables like green peppers are responsible for similar flavors in wine, for example.

Photo: Chris Kornman

The most popular theory as to the cause of PTD blames a unique species of bacteria given the species name coffeiphila (“coffee-lover”) that finds an entry point into the coffee seed by way of a break in the skin of the cherry, frequently caused by a small insect feeding on the fruit. A scientific study even noted that the bacteria “gave off a strong, potato-like odor.”

No matter the specific cause, the problem is localized regionally and originates at the farm level, well before the coffee is processed, exported, roasted, or consumed. And, importantly, this is not due to any deficiency or oversight on the part of the farmer or producer.

This creates an unfair double-standard, in my opinion. Taste defects such as mold, phenol, or quakers may occur under a plethora of adverse conditions. It’s highly uncommon to find roasters who stop buying coffees from an entire country or region as a result.

So given the opportunity, I prefer to double down, to purchase more coffee from trusted producers who are investing in their communities and in the economic and environmental sustainability of coffee.

That kind of commitment can be difficult, given the region’s instability. My 2015 trip was cut short as violent protests broke out in Bujumbura in response to two-term president Pierre Nkurunziza’s announcement that he would run for an unconstitutional third term. Ramadhan ushered me across the border, back to Rwanda, where I changed my flight. He returned to the capital to gather up his family and move them to the relative safety of Kayanza.

What comes next for the small country is hard to say. Agriculture and coffee in particular, remain an important source of income in Burundi. I think that the return of COE and the ongoing work of committed producers like Jeanine and Ramadhan will gradually elevate not just the exquisite flavors of coffees from the region, but also the livelihoods of those farmers producing them.

About Burundi

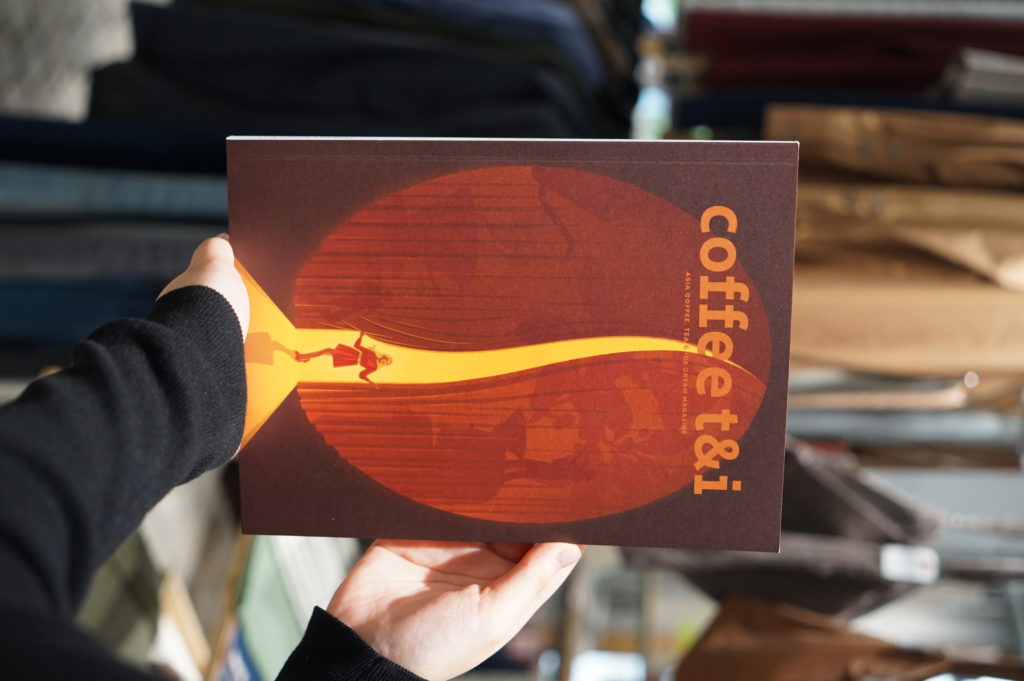

Burundi was announced as the 2019 Portrait Country earlier this year during the Specialty Coffee Expo in Boston with an aim to invite more people to discover “the undiscovered origin of coffee”. Coffee has played an eminent role socioeconomically for the country since the 1930s as a main source of income for its people.

NO COMMENT