This year has not been easy for people in the coffee industry, including 25 million smallholder farmers who are responsible for growing 80% of the world’s coffee. In total, 125 million people depend on coffee for their livelihood, from transporting and roasting the beans to selling the final product. Despite the difficulties in origin countries like finding sufficient migrant labor, even much smaller coffee-producing countries like Ethiopia, which exports about four million bags of coffee per year, have largely been able to continue production as planned. In many countries, including major producing nations such as Brazil and Colombia, workers in the coffee sector have been defined as essential workers who must continue to work during the COVID-19 pandemic.

At an international level, coffee producers, traders, and roasters have already seen significant changes in coffee markets. There have been increases in international coffee prices, with a strong likelihood of continued increases as countries stockpile coffee in case supply chains are hit harder by COVID-19. This could have a positive effect for coffee farmers who have until recently faced record low prices for their coffee, providing them with essential income that could go toward improving working conditions to make employment in the sector more attractive. However, coffee traders’ and roasters’ increased expenditures on coffee could decrease the amount of resources they have available for monitoring and remediating labor issues in their supply chains. Additionally, while the market price for coffee has increased, prices for fair trade coffee have stagnated, creating a risk of coffee producers abandoning fair trade schemes that promote decent working conditions. While there has been an increased demand for coffee sold by supermarkets, there have been steep decreases in demand for coffee sold at cafés, which is generally high-end or premium specialty coffee that brings much higher prices for farmers.

Production is very dependable on the last part of the coffee chain and its demand. That is why, when coffee shops close down even the best beans will stay in warehouses to rot. Luckily, online grocery retailers seem to have coped well with lockdown. Coffee was already the number one e-commerce grocery product before 2020 and the prevalence of subscription services and partnerships between delivery services and high-street chains have ensured customers could still get their hands on some. With people confined to working from home and with limited options to leave the house, making coffee was one of few ways to take a break from work.

Paying Back

Before you buy your morning cup of coffee, there is a big business process that needs to take place: harvesting coffee, washing, drying, selling, shipping, re-selling, roasting, selling again and finally griding and brewing. But what if this long chain can be simplified for the better living of the farms? We talked with Lewis Harding from Coffee Exchange to discover how coffee chain can be shorten and made more fair to all the participants.

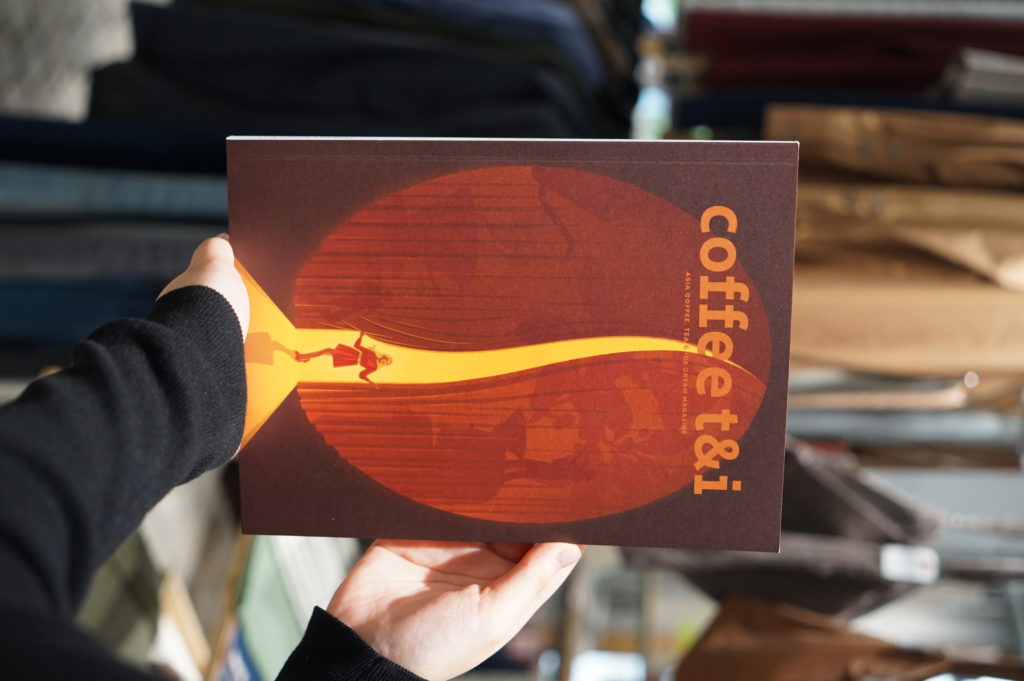

Lewis is originally from London and growing up, surprisingly for a British person, never drunk tea but was always more interested in coffee. With the degree from Queen Mary University in Business & Economics he first came to China back in 2008 to work in finance. Back then there was very little coffee except instant coffee and Taiwanese style coffee chains that where more like diners so seeing first Starbucks opening in China was very exciting for Lewis.

Simplifying the Supply Chain

Most coffee consumers see coffee as a generic commodity, but it is essential to our morning mood. This year coffee, which comes from some of the most economically challenged countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia, is being hit on all fronts, and hard. According to the International Coffee Organization (ICO), the coffee market remained relatively steady during the 2008 financial crisis, although consumers shifted to in-home consumption and purchased more affordable coffee. In a recent report, the ICO warns that none of the previous financial crises compare in terms of depth and breadth of COVID-19, and their analysis warns of an almost 1:1 relationship between global GDP and coffee consumption.

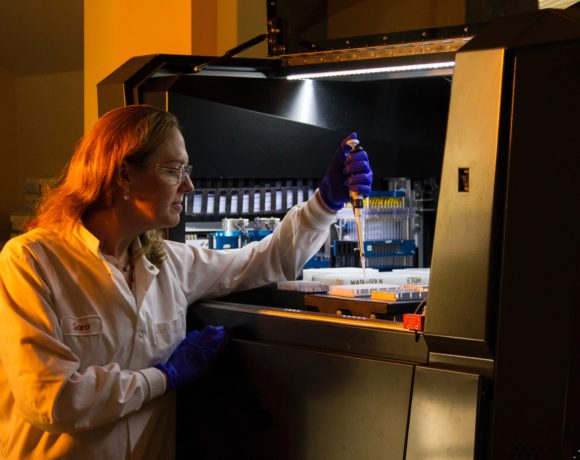

Here as what could help, direct trade comes to mind. Direct trade, albeit a fuzzy concept, is generally regarded as a positive and socially responsible practice in today’s coffee industry. Buying directly cuts out the middleman—coyotes and cooperatives alike—so more money stays with the farmers. But what about another trend: Large transnational roasters that set up branch offices to buy directly from smallholders, eliminating the middleman buyer yet paying the same low price. This is as direct as trade gets, yet it brings up some serious concerns surrounding justice and sustainability.

Being a coffee nerd, Lewis decided to quit his job in finance and start a business, It had to be in coffee this time. “I originally wanted to operate with roasted coffee and to be more unique, I wanted to source my own coffee from around the world. I spent several years travelling in Rwanda, Ecuador, Peru and several other countries developing relationships to be able to import their coffees into China. I also built relationships with a lot of Chinese roasters who were all interested in getting unique coffees direct from source.” It was at this time that he realized it was time someone built a B2B marketplace for the green coffee trade. And as Lewis was no strangerto building his own computer (back in 90s) and knew alot about IT, online B2B marketplace was a way to go.

The name Coffee Exchange was based on the idea of coffee producers being able to openly market and sell their coffees to interested buyers around the world. Lewis shared: “We’re not a traditional green coffee trading company—we don’t’ buy coffee, add a margin and then sell it on to roasters. We operate on a partnership model where we offer producers the chance to connect with roasters—we solve all aspects for producers to sell directly to roasters—these include market knowledge & coffee evaluations, logistics, fulfilment & warehousing and ultimately access to over 1500 roaster in China and around 30 in the USA.”

Acknowledging the Problem

Because coffee is a perishable item, ideally it would come directly from the farm to your doorstep, with as few intermediaries as possible. However, the current coffee supply chain is antiquated and inefficient, with up to 20 middlemen and six months between the farmer and you. Many coffee farmers have little market access, forcing them to rely on middlemen to bring their green, unroasted coffee to the market. With so many intermediaries, the typical coffee supply chain excludes farmers from the most profitable activities and is in dire need of optimization. Middlemen, and especially roasters, capture nearly all of the profit after the crop leaves the farm. It’s a stunningly disproportionate reward compared to the amount of time, labor, and know-how farmers put into their product.

Of the millions of coffee farmers worldwide, nearly 80 percent are small scale, often living on less than two dollars per day. In the communities we work with in northern Nicaragua, we have seen mothers choosing which of their two children can afford to go to school, women and men walking several kilometers to fetch water, and people flocking to the community center on the one day a doctor visits every few months. Although coffee farmers around the world spend years cultivating their crop and do an incredible amount of labor to grow and harvest their product, they typically receive less than $1.00 per pound (or the equivalent of about $0.03 per cup of coffee), which is then sold in the US for upwards of $20.00 per pound, keeping them trapped in a cycle of subsistence farming.

Stepping Up

“We work directly with producers in origin to consolidate shipments to the destination country. We then warehouse and sell coffee to roasters. We are also curating and sharing content from producers to enable roasters to share the coffee’s production story with their customers.” Coffee Exchange provides transparency reports with live data so one can engage with the market directly, without middleman. Producers who use the platform see the price they receive increase from 20-50%—this is a big difference in the low margin green coffee trade. These economies of scale and direct market access might be exactly what the industry needs in such challenging times.

The company now works with coffee producers from Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico and Indonesia, serving over 1,500 roasters in China where they can purchase coffee from around 50 different producers all over the coffee world. As coffee consumption in China is growing rapidly the team can see both of these metrics expand accordingly. “We’ve seen premiums paid to producer increase whilst at the same time providing coffee at better prices and of a higher quality that what’s in the market. However, with the relatively new sector of specialty coffee we have seen more interest in country specific—single origin—coffee.” So Coffee Exchange goes even further: they offer coffee that is often lot specific to a specific farm. “If you’re a coffee consumer who appreciates this difference, much like the fine wine industry, then whether your British, Chinese, Russian, American, Japanese or Korean then you will appreciate the unique flavour profiles these coffees offer. With that being said, you do see Asian countries opt for coffees with a stronger fruit and/or floral flavour profile,” says Lewis.

Coffee Exchange is intended to bring in transparency in coffee trade and maintain the traceability of coffee from bean to cup so as the consumer tastes the real coffee and the grower is paid fairly for his produce, win-win for everyone. As the Asian coffee market is growing between 4% and 5% a year, while the rest of the world is growing at between 2-2.5% a year, Coffee Exchange has been a great platform from producers from all around the world to be able to sell their coffee to satisfy the growing demand of Asian coffee drinkers while sustaining their production and finding new ways of doing business.

NO COMMENT